BALTIMORE – The British Royal family held their collective breath awaiting the skin pigmentation of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle’s children; meanwhile the sound that rippled across the pond revived the aged-old one drop rule debate in the United States.

Had their daughter Lilibet (pictured below) been born 100 years prior in Maryland, she would have been forced to live as a second-class citizen under strict rules that dictated a separate and distinctly inferior existence simply because her maternal grandfather was Black.

Marylanders had been living under the threat of detecting so-called Black blood since it was a colony and to some degree the rule remains today. By the early 1900s, with the Ku Klux Klan on one side and civil rights activists on the other, no one in Baltimore stood taller amongst the academic elite working to ensure the purity of the white race than John Whitridge Williams, a Johns Hopkins University (JHU) scholar.

Enter The Bull

After the abolition of slavery, the United States distinguished itself from England when it instituted and enforced Jim Crow laws. Segregation was necessary in order to subject the less desired class to an inferior existence. It was not an easy task to determine who descended from Africa to preserve the country’s white supremacy doctrines.

Called “The Bull” behind his back by students at JHU School of Medicine, Williams’ pedigree (grandson of Maryland enslavers) made him the perfect candidate to usher in codification of the “one drop rule.”

“His shoulders were unusually broad and his legs and feet unusually small. He had a characteristic, alert, short-strided gait, so that those of us who knew him well can still hear his walk as he hurried down the concrete floors of the hospital at three minutes after nine each morning.”

Alan F. Guttmacher, 1939 Johns Hopkins University Press on Dr. J. Whitridge Williams

The man who wrote the book on obstetrics was asked to birth a legal standard for Blackness. So highly regarded was the native Baltimorean that his influence extended beyond medical research to both judicial and legislative matters. The stage was set for “The Bull” to decide what some hoped would be the definitive case that would usher in eugenics policy.

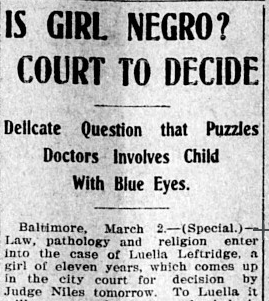

Bluest Eyed Black Girl

Williams appeared in court in 1911 to state with scientific certainty whether a “colored” orphanage was the proper housing for the blue-eyed girl with no known parents whose family wanted her moved because they said was white.

Baltimore’s segregated orphanages (including the one funded in the last will and testament of Johns Hopkins himself at the same time he founded the university and the hospital that both carry his name) have a particularly ominous place in the city’s history of institutional oppression.

Luella Leftridge by all accounts “looked white” to anyone who saw her. Nonetheless, the state’s legal system issued a writ of habeas corpus so that the Hopkins specialist could determine if Luella descended from African ancestors. Luella had pale skin, straight hair, and piercing blue eyes, according to court observers.

On one particular day inside a downtown Baltimore courthouse, “The Bull” gazed deeply into the 11-year old girl’s strikingly blue eyes. With zero hesitation, the doctor told the judge if there was indeed one drop of “negro blood” anywhere in Luella, it was not visible to him.

All that hung in the balance was the future of race-based societal constructs infused into the DNA of the country: subjugation, oppression, incarceration and segregation. It took very little prodding to lure the grandson of enslavers1 into the raging debate of the day on whether the existence of “Black blood” could be scientifically proven.

“Line of demarcation between the whites and negroes is point to be settled”

21 February 1911 Baltimore Evening Sun

The Test For “Negro Blood”

Segregationists were keen over the prospect of having case law settle the concept of racial purity. Furthermore, a favorable racial ruling based on science instead of morality could bolster the enforcement of the Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” ruling decided just about a decade earlier.2

The entire nation was riveted. The plight of young Luella was splashed in newsprint in many southern states’ papers including Mississippi and North Carolina.

Hopkins applied medical jurisprudence’s four tell-tale characteristics of what it meant to be Black to the 11-year-old (thought to be) orphaned girl. Initially, Luella was deemed white because she did not exhibit any of the following:

Of minor concern to the medical community was that Luella actually displayed a fourth characteristic of Blackness: a barely perceptible shadow of a half-moon below the surface of one solitary fingernail. However, the consortium of doctors ruled that since Luella did not present three of the four for Blackness, she was deemed white (enough).

Complicating matters was that a strikingly beautiful 19-year-old young woman (who appeared white) fought for her sister to be released from St. Elizabeth’s Colored Orphanage and Asylum. Elizabeth Leftridge herself had been an “inmate” for several years at St. Elizabeths, an orphanage that held Luella since she was four years old.

“The Bull” said without equivocation: Luella was white. In contrast, officials at the orphanage that housed only “colored children” held steady with their belief that at least one of her parents was Black, which made her Black regardless of her blue eyes.

“He wielded a tremendous power on the [Johns Hopkins] Medical Faculty and in the whole domain of American obstetrics” wrote former eugenics society vice-president Alan F. Guttmacher in 1939, about his close friend and follow obstetrician.

Williams’ pedigree notwithstanding, his conclusion that Luella was erroneously placed in an institution with all Blacks was not embraced by the legal community. Instead, an entire team of physicians was consulted. Just to be safe.

The medical experts all fell in line behind “The Bull.”

The attorney for St. Elizabeth’s orphanage and asylum, Charles J. Bonaparte3, scoffed at the medical experts’ “superficial indications” that led them to conclude Luella’s blood was free of African ancestry. Instead, they believed the information received during the admission process that African ancestry was visible in the girls’ parents. They would have to find more relatives.

With little fanfare, the court abandoned science and resorted to the centuries-old one drop rule and kept Luella confined.

Tracing Luella’s Bloodlines

Baltimore’s quagmire made national news. The court could not risk seeming to be unsympathetic to an orphaned white girl tragically forced to live among the “lower race of people” on Baltimore’s west side. Nor could the court appear to be endorsing the jumping of social class by “passing.” Black girls ought not to be rewarded for fraudulently receiving all the privileges bestowed upon passing as a white woman.

Whatever appetite the southern elite had for a scientific process to determine race, it all waned once the credibility of a heralded institution was challenged. At stake was the uninterrupted brutal enforcement of Jim Crow‘s separate and unequal codes that systematically oppressed anyone with suspected Black ancestry.

Perhaps more importantly, white men had to be protected from being tricked into marrying someone of lesser worth and fathering Black children.

The orphanage located the girls’ paternal aunt, a Black woman living outside of Pittsburgh. She testified that her brother, married a white German woman and Luella and Elizabeth were half Black and half white.

Ultimately, the judge decided that Luella must stay in the substandard orphanage designed to hold only Black children.

In the starkest of terms, Judge Alfred S. Niles’ court embraced the one drop rule which had served white supremacists well since their beloved Antebellum days.

Maryland, as did other southern states that legalized slavery, had greatly benefited from the rule that counted children as part of the Black race if either of their parents had at least one Black grandparent (of any degree of African ancestry).

Not Really Loving Interracial Marriages

Despite Williams’ failure in making race determination a science, in the end, all parties were united in keeping Black and white children separated until the Supreme Court in 1954 decided the practice must end because of its unconstitutionality.

However, it remained illegal for any Black man to marry a white woman in Maryland until the Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional in the 1967. Colonial Maryland has the distinction of having the first ever legislation banning miscegenation.

"All marriages between a white person and a negro, or between a white person of negro descent to the third generation, inclusive, are forever prohibited and shall be void; and any person violating the provisions of this section shall be deemed guilty of an infamous crime and punished by imprisonment in the penitentiary not less than eighteen months nor more than ten years"Section 200, article 27 Code of Public General Laws state of Maryland

Fast forward 100 years since the 1911 Luella case to 2011 to when Oscar winning actress Halle Berry evoked the one-drop rule in a custody case with her daughter’s father. Berry’s daughter, a French-Canadian actor.

Berry cited that since her own father is Black, that makes her daughter Black as well even though the child’s other three grandparents are white. Her argument was that you deserved full custody in order to impart the importance of Black culture on her mixed-race daughter. J. Whitridge Williams must be turning in his grave.

1J Whitridge Williams’ grandfather (John Whitridge) was also a physician as well an enslaver. His grandfather was born in Rhode Island in 1791, relocated to Maryland in 1820. He is listed as the owner for people enumerated on the 1850 and 1860 census slave schedule.

2 The Supreme Court ruling on Plessy v Ferguson in 1896 that permitted Louisiana rail cars to segregate accommodations based on race set for the separate but equal doctrine that became Jim Crow.

3Charles Bonaparte, the Baltimore-born lawyer who represented the orphanage in the Luella case was a former US Attorney General in President Theodore Roosevelt’s cabinet. His grandfather was Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother.

Next up: Eugenics Takes Hold in Baltimore