BALTIMORE – Every potential eyewitness present when surgeons covertly transported a 23-year-old Black woman from a New York mental asylum to a hospital down south just so that they could experiment on her brain – are all now dead.

While the victim’s name was never intended to be disclosed, with the benefit of time and the advent of the Internet we now know her name is Ida Jones. The young woman was brought to Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) during the summer of 1910 and returned to New York in a pine box (minus her organs). This is but one example of how Hopkins became known as the body snatcher hospital.

The Pituitary Body and Its Disorders

Although the details of Jones’ demise have been buried for over a century, parts of her brain (along with hundreds of others) are open for casual public viewing as part of a collection of human remains on display at Yale University’s library.

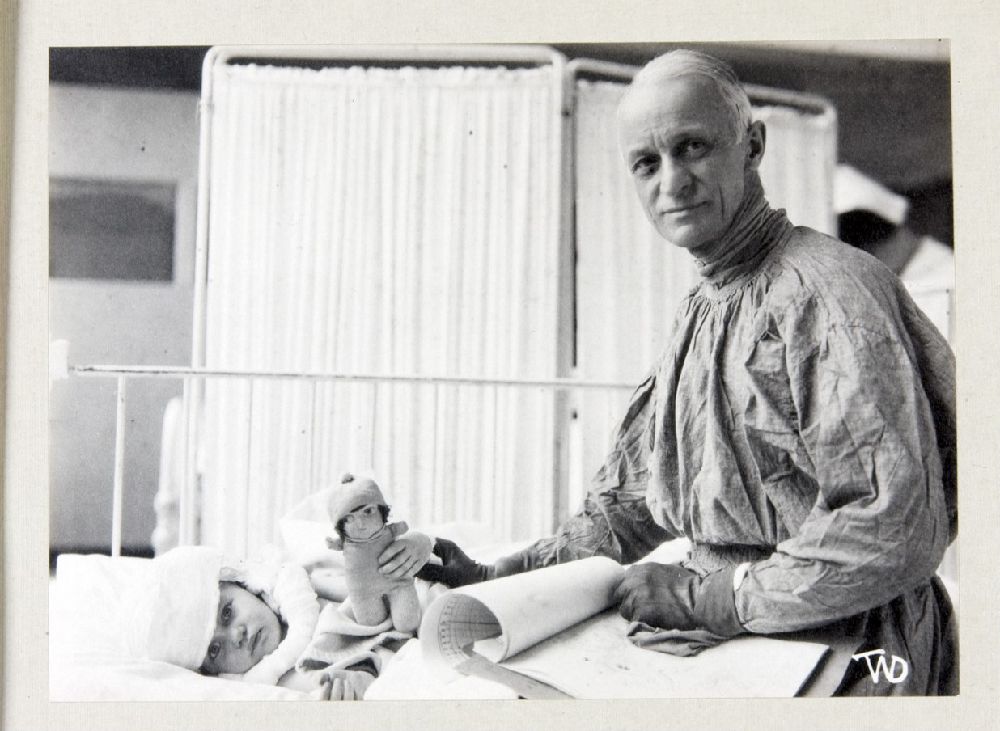

Ida Jones arrived at the racially segregated hospital not as a patient but as the intended lab rat for the celebrated “father of modern neurosurgery.” Harvey Cushing, head of Hopkins’ newly opened Hunterian Experimental Surgical lab, was an expert surgeon on dogs and monkeys before the institutionalized Black woman was delivered to him. Hopkins’ officials, eager to compete with Ivy League teaching hospitals up north, enthusiastically supported Cushing’s quest to forge a new surgical frontier specialty1.

In addition to Jones’ remains, the museum in Yale library’s Cushing Center is the final resting place for brains removed from over 2,000 Cushing’s patients spanning his 35-year career as a neurosurgeon at medical schools at both Hopkins and Harvard University. In some cases, brains were removed without the patient’s knowledge and often in opposition to the family’s consent.

Generations of Baltimoreans have heeded the warning to steer clear of Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) at night fearing being snatched for medical experiments. Public officials and newspapers routinely dismissed the Blacks’ fear of roaming “night doctors” as tales of ignorance. For Baltimoreans of African ancestry, surviving fractured families using collective memory is a time-honored tradition. Passing along oral history has not only kept unsuspecting victims safe, but the lack of media acknowledgment adds yet another layer of trauma to urban existence.

Had it not been for Cushing’s dedication to documenting every step towards building his Brain Tumor Registry that he hoped would be his lasting legacy, we might not have ever known what happened to Ida Jones or be able to piece together the story of the human remains that Cushing collected. Most of what we know about the crimes of Cushing comes from his very own words, his dedication to taking photographs, and those who knew him best.

Exhibit A: The Deceased

As an inmate at the massive mental health asylum in New York City known as Wards Island, Jones was selected as a surgical experiment candidate on the recommendation of Cushing’s friend. As good fortune would have it (for Cushing), the Hopkins doctor was in need of surgical case studies for a lecture planned for later that year.

Ida Jones was brought to the east Baltimore hospital in the custody of New York City officials reportedly with complaints of headaches and failing vision on June 20, 1910. Ten short days later she was lying dead on the operating table with Cushing holding the bloody scalpel. X-Rays did not reveal any evidence of a “brain tumor” for case number XLII2.

Before Cushing arrived as a medical resident, Hopkins had attempted only two brain surgeries because of the mortal dangers. Surgery conditions were primitive with no monitoring system and anesthesia was often an afterthought.

The first of Ida’s two operations, Cushing caused massive and uncontrollable bleeding while cutting through the brain’s dura layer. Ida stopped breathing on multiple occasions, and she was resuscitated during the hours-long event. It was miraculous that Ida survived the first surgery on June 25, 1910.

A second operation was attempted on the 5’3” young woman five days later. Ida J bled out and died on the operating table, Cushing confessed in his book. However, a more antiseptic version is provided on the certificate he signed. Cushing blamed her death on a “brain tumor.”

On the certificate, the petite native of North Carolina is listed as married, a New York City resident, with no parents’ names provided. Her remains were reportedly sent to New York City on July 4, 1910, for burial.

In contrast, the 1910 federal census depicts Ida as an unmarried 22-year-old inmate at Ward Island. At the time, Ward Island was the largest hospital in the country with over 5000 patients on its grounds that covered 320 acres in Manhattan. Under the guidance of Adolph Meyer human experimentation without consent or caution was the norm instead of the exception.

It is assumed that Ida’s remains are buried unmarked in a mass grave in one of the city’s potter’s fields.

Surgeon or Serial Killer?

Cushing often got away with murder. The evidence was kept in a private little black book that documented each death that was different than the data he published.

While at Hopkins, his patients’ mortality rate is often described as abysmal but without specific data. “[Cushing] seems to misstate his operative deaths,” wrote his biographer Michael Bliss.

Feuds erupted within the walls of Hopkins about Cushing’s lack of “scientific integrity.” Cushing complained to his father about negative press that lampooned his inadequacy based on the series of deaths that stemmed from numerous and consecutive fatal operative attempts.3

Hopkins provided little structure and often failed to reign in its young surgeons. “[Cushing] made significant mistakes. Pictures and descriptions of some of his cases suggest a tendency to overclaim for his organ [pituitary], that he may have been too eager to label a fat boy or a big man a pituitary problem,” wrote Bliss.

Cushing was not above ending the life of patients as Christopher Wahl wrote in his 1996 dissertation: “Not only does Dr. Cushing take action to euthanize his unfortunate, decerebrate patient, but he thinks nothing of revealing his intention in the operative note. By the standards of medical care today, Cushing’s actions would be morally and legally indefensible; in 1913, he could act with impunity”.

Assuredly Cushing’s actions would land him in prison today. On two different occasions Cushing used a baby’s brains in attempt to save the life of a wealthy and well-connected man from his home state of Ohio. When news agencies learned of the first brain transplant attempt, Hopkins officials issued an “indignant denial” that any such procedure had taken place, according to Bliss’s 2005 biography.

When news agencies learned of the brain transplant attempt, Hopkins issued an “indignant denial” that any such procedure had taken place.

Michael Bliss, Author, “Harvey Cushing A Life In Surgery”

The Ohio businessman (whose wife’s father was the grandson of ex-president William H Harrison) had been in a coma at Hopkins for nearly six months. William T. Buckner, twice received the pituitary of infants delivered at Johns Hopkins Hospital a procedure funded generously by his wife.

The first transplant failed, according to news accounts, because too much time passed between the infant’s death and the transplant. Hopkins procured the second infant (who died from malnutrition) with hardly any time passing before initiating the transplant. A brief mention indicates that they obtained the parent’s consent, but that is not substantiated, nor likely.

both Cushing and Johns Hopkins Medical School.

Exhibit B: An Active Crime Scene

Perched precariously between the promise of Pennsylvania’s freedom to the north and the seat of the Confederacy to its south, even today Baltimore remains an active crime scene, generations in the making.

Ida Jones took her last breath at Johns Hopkins Hospital, named for the wealthy Baltimore financier and enslaver. From its inception, Johns Hopkins institutions (the University and Hospital) have been one of unimaginable deceit, denials, and mythmaking that started with erasing enslaver from his official historical record.

Even while Hopkins’ parents and grandparents forced enslaved families of African descent to labor from birth to death on their Maryland tobacco plantation, Blacks were being transported through Maryland for risky medical experiments further down south. In her book Medical Apartheid, author Harriet Washington refers to the abundance of “clinical material” forcibly removed from people of African descent that fed medical research and medical training in the United States.

Another Black woman, Henrietta Lacks, unwittingly had her Cancer cells collected by Hopkins researchers after her 1951 death. Hopkins later shared the specimens with doctors around the globe without the knowledge or permission of her husband and children. Her family’s pursuit for justice continues today. Hopkins was also involved in the decades-long syphilis experiments at Tuskegee3.

With each passing decade, the more difficult it is to prove the elements of a crime, let alone one conducted in the privacy of a hospital surgical ward. The smoking gun in Cushing’s case remarkedly was his own published words.

The Verdict

Neither Hopkins nor Yale have commented on growing efforts to remove human remains of oppressed people from public collections, like the Smithsonian. Since the collection of brain specimens was brought out of its sub-basement in 2010, Yale University began exploiting the stolen remains by extracting DNA for additional study.

The Hunterian Lab today still exists but with modern facilities.

End Notes

1. In a major address in 1908 St Louis, Cushing described the over 300 craniotomies he performed in less than a decade when there had just been two in all the years prior to his arrival at Hopkins although 32 tumors had been identified and 13 had been referred to surgery. Christopher Wahl Dissertation.

2. The year before Ida was included in the 1912 publication about the pituitary that garnered him widespread attention, Cushing spoke about her at a New York gathering. Cushing also thanked the hospital’s pathology department for stepping aside and allowing him free reign over all the pathology of patient specimens (even those who died at his hand) without their interference.

3. Once the Tuskegee experiment story broke that revealed how Black men were left untreated for syphilis and permitted to die a long, slow death, the federal government responded to the crisis by requiring institutions who receive federal funding to have an “Institutional Review Board.”

Bibliography

Bliss, M. Harvey Cushing. A Life in Surgery. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Cushing H. The Pituitary Body and Its Disorders, Clinical States Produced by Disorders of the Hypophysis Cerebri. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott. 1912 [Google Scholar]

Fulton, J. Harvey Cushing: A Biography. The Classic of medicine library. 1946. [Internet Library]

Pendleton C, Adams H, Mathioudakis N, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Sellar door: Harvey Cushing’s entry into the pituitary gland, the unabridged Johns Hopkins experience 1896-1912. World Neurosurg. 2013 Feb;79(2):394-403. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.12.007. Epub 2011 Nov 11. PMID: 22079823; PMCID: PMC3936577.

Wahl. C J. The Harvey Cushing Brain Tumor Registry: Changing scientific and philosophic paradigms and the study and preservation of archives. A thesis submitted to the Yale University School of Medicine in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Medicine, 1996.

Washington, Harriet A. Medical Apartheid. Random House, 2019.